By Martin Jones

In this extensively researched perspective on British imperialism, Caroline Elkins draws out a pattern of deliberate and sanctioned violence, inflicted on numerous communities, over a period of two hundred years. What started as a study of latter-day imperialist Britain in Palestine, Malaya, Kenya, Cyprus and Aden eventually tracked back to the precursor ventures in India, the Caribbean, South Africa and Iraq. Elkins documents how, under the banner of a liberal imperialist enterprise to civilise and bring good governance, not only have individuals and societies around the world suffered sustained violence under British colonial rule but the legacy continues to work its effects today.

Elkins’ thesis explains how there were two contradictory forces at the heart of the liberal imperialist endeavour: reform and coercion. Violence, claims Elkins, ‘was endemic to the structures and systems of British rule;’ violence ‘resided in liberalism’s reformism, its claims to modernity, its promises of freedom, and its notion of law – exactly the opposite places where one normally associates violence.’ On the one hand was the imperial “civilizing mission,” on the other, the implementation of the necessary force to propel forward these “backward” cultures towards the ideal that Britain, it was claimed, embodied. Thus Kipling’s framing of the “White Man’s Burden,” to serve the needs of “Your new-caught, sullen peoples, Half-devil and half-child.”

Tracing the continuities of these forces of coercion through the British imperial endeavour, Elkins demonstrates how systems and processes were developed to cope with particular imperial crises and subsequently deployed in other locations facing similar conflicts. In Malaya, for instance, to counter insurgents utilising support of local communities, Britain, in 1950, launched the Briggs Plan to forcibly relocate the rural population. “New Villages” were created, surrounded by barbed wire and watchtowers and controlled by the police. The original villages of the displaced peoples were burned down. A similar approach, named “villagisation,” was subsequently implemented in Kenya in 1954, relocating over one million Kikuyu over a period of eighteen months. In fact this same approach, under the advice of Robert Thompson who had worked on the counterinsurgency plan in Malaya, was adopted by the South Vietnamese government in 1962; the “Strategic Hamlet Program” corralled over 4 million people into more than 3,000 hamlets. These approaches have echoes of the concentration camps of women and children masterminded by Kitchener in South Africa in the early 1900s, rounding up more than 100,000 Afrikaners, of whom over 30,000 died through malnutrition, starvation and disease. This development of techniques and their transfer across locations, along with experienced personnel, was typical as crises developed throughout the history of the empire.

Forced location was but one of the many actions based on coercion and violence. Elkins documents the multiple horrors carried out. Villages were burnt down or subjected to aerial bombings, as in Iraq in the 1920s and the North-West Frontier; collective punishment was implemented, including twenty-two-hour curfews, “food denial” and destruction of crops. Thousands were deported, while individuals were subjected to physical and sexual violence, numerous forms of torture – on occasions leading to death – and arbitrary killings. In order to absolve the individual decision-makers in civil and military authority and those executing these atrocities on the ground, existing laws were amended or new laws introduced, on occasions enacted in retrospect. Elkins terms this ‘legalized lawlessness.’ When called to account, authorities would justify their actions on the basis of maintaining law and order, claiming the “moral effect” of violence. Or they would proceed as Churchill did when, as secretary of state for war, he described the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre (the Amritsar massacre) as “an event which stands in singular and sinister isolation” – thus excusing the occurrence as exceptional and untypical and in consequence of no ongoing concern.

In addition to the identification of violence as endemic to liberal imperialism, key aspects of Elkins’ work are her archival research, discovering original correspondence from the 1950s, and her role in providing evidence in the Mau-Mau compensation court case which drew on the research for her 2005 book ‘Imperial Reckoning’. This led to the British government announcing the existence of previously unacknowledged documents, neglected due to ‘administrative mismanagement.’ Elkins’ research and that of her team in assiduously accessing and interrogating documentation provide the means for opening up new perspectives on British imperialism. Of course her work has been challenged and has been subject to criticism from other academics. But what is evident is that Elkins has provided a distinct perspective of British Imperialism, one that has produced concrete outcomes. In 2013 the British Government agreed compensation to over 5,000 Kenyans who “were subject to torture and other forms of ill treatment at the hands of the colonial administration” during the Mau-Mau insurgency.

Elkins makes a persuasive case for the contradictions of the liberal enterprise. The history of the trail of conflicts that British imperialism propagated is a fundamental background to many of the conflicts in today’s world, while the techniques of violence that were used and developed can be seen as progenitors of what we hear about and see in contemporary conflicts. Elkins’ work shines light on these histories, a work of assiduous labour that should be widely recognised; it is another step in revising our understanding of the British imperial past, challenging the attitudes that underwrite our current society, and a spur to continue the fight that has to be maintained today and tomorrow to hold those in power to account.

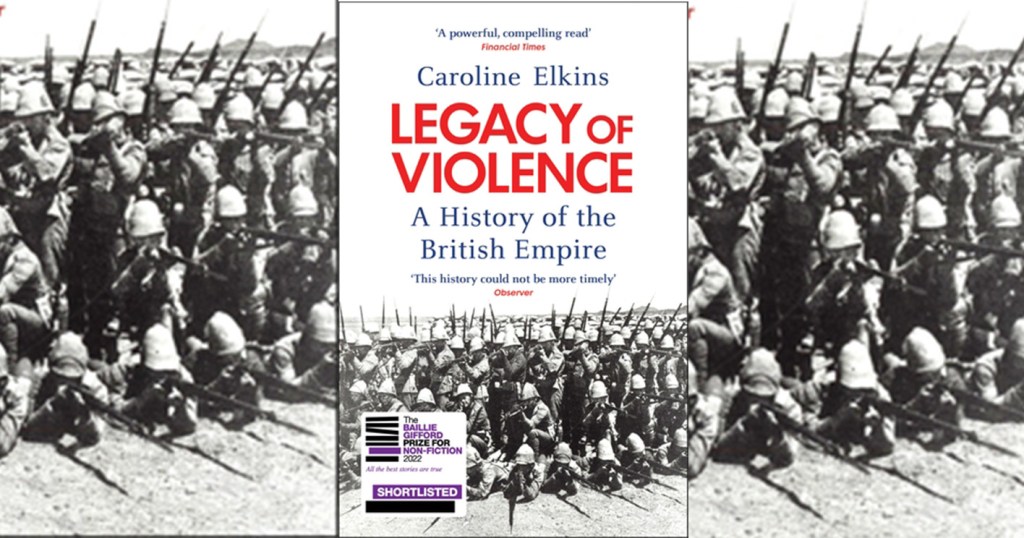

Legacy of Violence : A History of the British Empire by Caroline Elkins (2022) is published by Penguin (Vintage)

Martin Jones is a Liberation member

Interested in a reviewing a book for us? Or a film, play or exhibition? Get in touch at info@liberationorg.co.uk

Support our work – donate, become a member, affiliate your local organisation’s branch or volunteer

The views expressed in the articles published on this website do not necessarily represent those of Liberation.